It probably started with kids throwing paper airplanes from the top of a hill. Watching the folded piece of paper float through the air would have sparked a million ideas. This simple gesture, and the simple means by which the paper airplane was made, became the starting point for what is now the fastest way to cross continents.

Aviation is permeated by all forms of printed matter: charts, load sheets, records, magazines, luggage labels, timetables, certificates, hand fans, boarding passes, safety cards, posters, passports and of course, maps. You can roughly divide their purpose in two. One is functional, acting to support the operation of the flight, like the paperwork that must be completed prior to take-off, or the cockpit binder packed with charts and vital information. The other is what we as passengers encounter and sometimes require for our journey, from the passport — proof of who we are and where we come from — which can either open doors or close them, to the flimsy little baggage label, attached pre-flight.

Magazines and timetables

The touch points of travel are now mostly digital. The inflight magazine is just about hanging on for dear life. British Airways’ inflight magazine is no longer available onboard, instead it can only be found in their lounges, making it out of reach for most people. Singapore Airlines no longer makes a printed version of Kris World. The magazine has moved entirely online and is now accessed via the inflight entertainment system. When this was done, it was heralded as a great day for sustainability. And although it’s true that replacing paper magazines with a digital edition will save weight and ultimately fuel, something is surely lost in this translation.

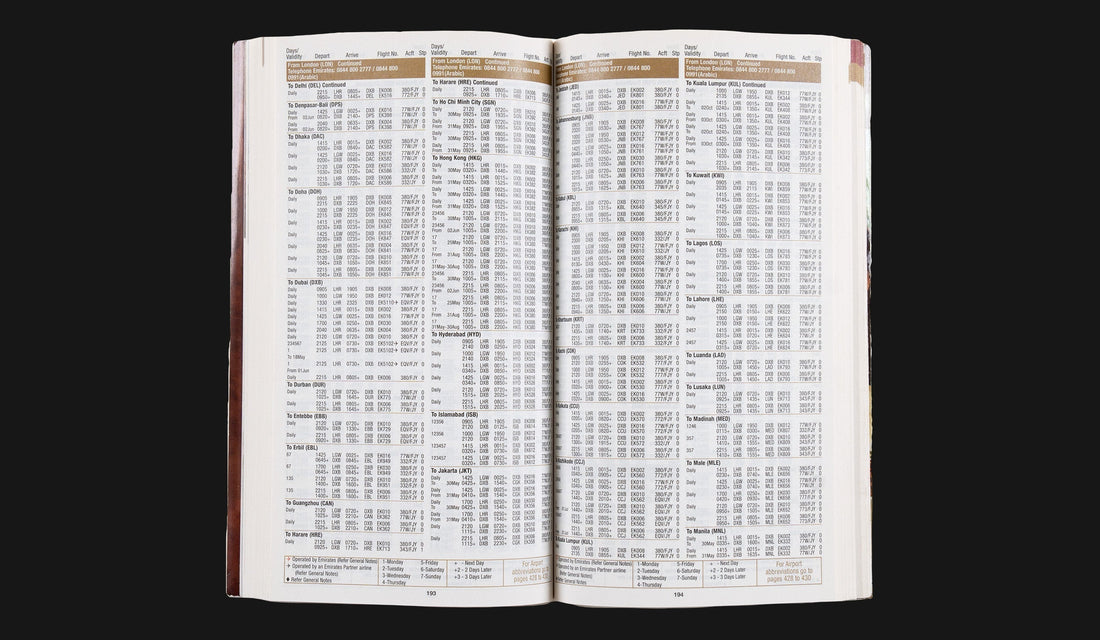

Emirates has stopped making printed timetables. Its last edition from 2015 featured a promotion for its Wi-Fi network on the frontpage like a premedition of what was replacing it. Today it would seem almost mad to print one, as route networks change so quickly that by the time it’s produced, it’s out of date.

Japan Air Lines Hand fan wrappers. These were handed out to mark the crossing of the Equator and the International dateline

The assorted paper we encounter on our journey can seem quite ephemeral, but some bits linger. Months after completing a cross Atlantic trip, you may pick up the jacket you wore on your journey and discover a discarded boarding pass in its pocket, an instant reminder of the flight. It is also comforting to board a flight to Singapore and be offered a copy of the South China Morning Post, the local newspaper at your destination. A thick wad of local news takes you immediately there, before you are even airborne.

The Australian singer Nick Cave once released an album which started life as notes scribbled on the back of airline sick bags. When you need something to write on, anything will do and there is something sublime about repurposing the sick bag for poetry.

Sometimes when I see people in transit carrying luggage with the label still attached, I try to work out where they have been, from the airport code printed alongside the barcodes. I imagine what they were doing there in Las Vegas, Hong Kong, Grenada in the brief moments when our paths crossed.

A printer in the sky

Up at the business end of the aircraft, things are also going paperless. However, when you start your flight training, you may be surprised to know that it is a very analog affair. Routes are plotted on a paper chart; calculations are written down on pieces of paper. Nothing during these early days of flying is digital. In fact, analog is the only way to master the basics. It is only much later that you can start to consider replacing these traditional methods with their digital equivalent.

Modern planes today are very digital creatures, from crisp digital displays, some even with touch-screen control, satellite navigation and digital check lists to airport diagrams embedded into the cockpit displays. You might, however, be surprised to find a small printer installed in most cockpits. This allows pilots to print air traffic messages, fuel predictions and much more. Even with all the digital advances available, it’s reassuring that pilots have the option to print things out. It’s better for your eyes too, but I wouldn’t want to fix a paper jam at 38,000 feet.

A boarding pass/snippet from Interflug the East German airline

On the ground, printed matter and aviation continue to overlap in a more basic way. In most secondhand bookshops there is a section devoted to aviation; this is not, however, where some would have you believe books go to die. No, this section of the bookshop can be a treasure trove of the odd and peculiar, books that for some reason, people have been unable to rid themselves of.

Bookshops at airports tend to be quite busy, perhaps because there isn’t much else to do than browse books while you wait to board but there could be other reasons. Airplanes make for great places to read. If you are flying solo you can pretty much be in your own world for the duration of your flight with the constant hum of the engines providing a comforting background noise. There is also the imposed lack of any sort of internet connectivity (mostly). This then makes it a great place to be undistracted and during daylight hours you automatically get the best reading light anyone could ever ask for, the unblemished stark sunshine outside your window.

That tranquility is now under threat from inflight wifi. Deeper inside some of those bookshops, nestled alongside the airplane-friendly sized deodorants, you may find the magazine stand. There, next to copies of The New Yorker you will find the title, Flight International. Once a weekly publication, this proud magazine has covered aviation in all its forms since it was first printed in 1909 – six years after the Wright Brothers first took to the sky, that’s 113 years of continuous publication.

Paper airplanes

Back to basics. Japan Airlines has a tradition that dates back decades, wherein newly graduated cabin crew throw a paper airplane into the sky together as part of their graduation ceremony. Often attended by the CEO of the airline, it’s a joyous occasion, a shared moment that takes place in a hangar at Haneda airport. This fascination represents perhaps the most basic form of flying. It is so immediate - in less than a minute you can construct something with the ability to glide through the air on an unknown path. It is a fascination not lost on millions of kids, as well as a whole generation of artists.

Two books from two very different authors. 1. Wolfgang Tillman's Concorde from 1997. 2. Le Corbusier's Aircraft originally published in 1935 (Here's as a reprint).

The American artist and anthropologist Harry Everett Smith was an obsessive collector of many things, including paper airplanes that he came across in New York. There is something very joyful about looking at photos of his collection. Each paper plane is made by a different child, thrown from a different vantage point. It includes paper airplanes made from all sorts of paper - children’s drawing paper, grid paper and newspaper – each leaving the child’s hand on some sort of trajectory, often unpredictable.

In 2015, Dutch artist Sjoerd Knibbeler published a book called Paper Planes. It unfolds to be one long concertina. On one side the book outlines various aircraft types, from jet fighters to drones. It breaks down their technical merit and successes. On the flip side, he reconstructs their aerodynamic shape using just a single piece of paper. It is a glorious simplification of their aerodynamics which completely humanizes them, even if they have been designed to be killing machines.

This piece originally appeared in Volume 2 of Direction of Travel.